Embark on a journey into the realm of pristine audio with our comprehensive guide on How to Edit Audio to Remove Background Noise. We will illuminate the common culprits that mar your recordings, from the subtle hum of electronics to the distracting chatter of an environment, and explore why their elimination is not just a preference but a necessity for professional-quality sound.

Understanding the nuances of various noise types, such as the distinct characteristics of hiss, hum, and ambient sounds, is the first step toward achieving crystal-clear audio. This exploration will delve into the technical distinctions that set these noises apart, providing you with the foundational knowledge to tackle them effectively.

Understanding Background Noise in Audio

In the realm of audio production, clarity is paramount. Whether you are recording a podcast, a voice-over, a musical performance, or even a crucial business meeting, unwanted background noise can significantly degrade the listening experience and undermine the overall quality of your work. Understanding the nature of this noise is the first step towards effectively mitigating its impact.Background noise refers to any sound that is not the intended subject of your audio recording.

These extraneous sounds can range from subtle environmental hums to disruptive sudden noises. Their presence can make it difficult for listeners to focus on the primary audio content, leading to fatigue and a perception of unprofessionalism. Effective noise removal is therefore not merely an aesthetic choice, but a fundamental requirement for professional audio.

Common Types of Background Noise

Audio recordings can be affected by a diverse array of unwanted sounds, each with its unique characteristics and impact. Identifying these noise types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate removal techniques.

- Hiss: This is a high-frequency, continuous, and often broadband noise, commonly originating from electronic components in recording equipment, such as microphones or preamplifiers. It can sound like a gentle “shhh” or a more pronounced static.

- Hum: Typically a low-frequency, tonal noise, hum is usually caused by electrical interference, often at 50Hz or 60Hz (depending on the local power grid frequency). It can manifest as a steady, deep drone.

- Ambient Sounds: These are the sounds of the environment in which the recording takes place. This category is broad and can include:

- Room Tone: The inherent sound of an empty or occupied space, often a subtle, low-level broadband noise.

- Traffic Noise: Distant or nearby sounds of vehicles, including engines, horns, and tires.

- HVAC Systems: The operational sounds of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning units, which can be a steady hum or intermittent whooshing.

- People Talking: Unintended conversations or general crowd noise in the background.

- Environmental Elements: Sounds like wind, rain, birds, or the rustling of leaves.

- Clicks and Pops: These are short, sharp, transient noises. They can be caused by physical disturbances to the recording medium (like a vinyl record), faulty cables, or digital glitches.

- Reverb and Echo: While not strictly “noise” in the same sense as hiss or hum, unwanted reverberation and echo occur when sound waves bounce off surfaces in a room, creating a sense of space that can muddy the primary audio.

Impact of Background Noise on Audio Clarity and Quality

The presence of background noise can have a detrimental effect on the intelligibility and overall appeal of your audio. The severity of this impact depends on the type and intensity of the noise relative to the desired audio signal.Background noise, particularly when it overlaps with the frequency spectrum of speech or music, can mask important details and reduce intelligibility. For instance, a subtle hiss can obscure the nuances of a vocal performance, making it sound distant or muffled.

A persistent hum can create a distracting, unpleasant foundation that detracts from the intended sound. Traffic noise or other ambient sounds can interrupt the flow of speech, forcing the listener to strain to understand. Even low-level ambient noise can accumulate over longer recordings, leading to listener fatigue.

Reasons for Removing Background Noise

Removing background noise is a fundamental and often indispensable step in audio production for several critical reasons, all aimed at enhancing the final product and ensuring its effectiveness.The primary goal of removing background noise is to improve the clarity and intelligibility of the intended audio. When noise is reduced, the desired signal—whether it’s speech, music, or sound effects—becomes more prominent and easier to discern.

This leads to a more professional and polished final product.Furthermore, effective noise reduction is essential for listener engagement. Obtrusive background noise can be incredibly distracting and can lead to listeners abandoning your content. By providing a clean and clear listening experience, you retain the audience’s attention and ensure your message is received as intended.In many professional contexts, such as broadcast, film, and commercial audio, a certain standard of audio quality is expected.

Background noise can make a recording sound amateurish and unprofessional, negatively impacting the perception of the creator or brand.

Technical Characteristics Differentiating Noise Types

Understanding the technical attributes of different noise types allows for more targeted and effective removal strategies. These characteristics often relate to their frequency content, temporal behavior, and source.

| Noise Type | Frequency Characteristics | Temporal Characteristics | Typical Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hiss | Broadband, predominantly high frequencies. Covers a wide range of frequencies without distinct tonal peaks. | Continuous and relatively constant. Can fluctuate slightly but is generally present throughout the recording. | Electronic components (microphones, preamps, tape saturation), digital signal processing artifacts. |

| Hum | Narrowband, typically a fundamental frequency (e.g., 50Hz or 60Hz) with harmonic overtones. | Continuous and steady. Often a distinct, audible tone. | Electrical interference from power lines, faulty grounding, transformers. |

| Ambient Sounds (e.g., Room Tone, Traffic) | Broadband, can vary significantly depending on the source. Room tone is often low-frequency dominated. Traffic noise can have a wide spectral range. | Can be continuous (e.g., HVAC) or intermittent and variable (e.g., traffic, voices). | Environmental factors, HVAC systems, street noise, human activity, natural elements. |

| Clicks and Pops | Very short bursts of broadband energy, often with significant amplitude. | Transient, extremely brief. | Physical damage to media, cable issues, digital data errors, handling noise. |

| Reverb/Echo | Affected by the acoustic space. Can manifest as delayed repetitions of the primary signal or a general sense of spaciousness. | Dependent on the distance and characteristics of reflective surfaces. | Acoustics of the recording environment. |

Each of these noise types presents a unique challenge. For instance, removing broadband hiss requires different techniques than eliminating a specific tonal hum. Similarly, transient noises like clicks and pops are addressed with methods distinct from those used for continuous ambient sounds.

Identifying and Isolating Background Noise

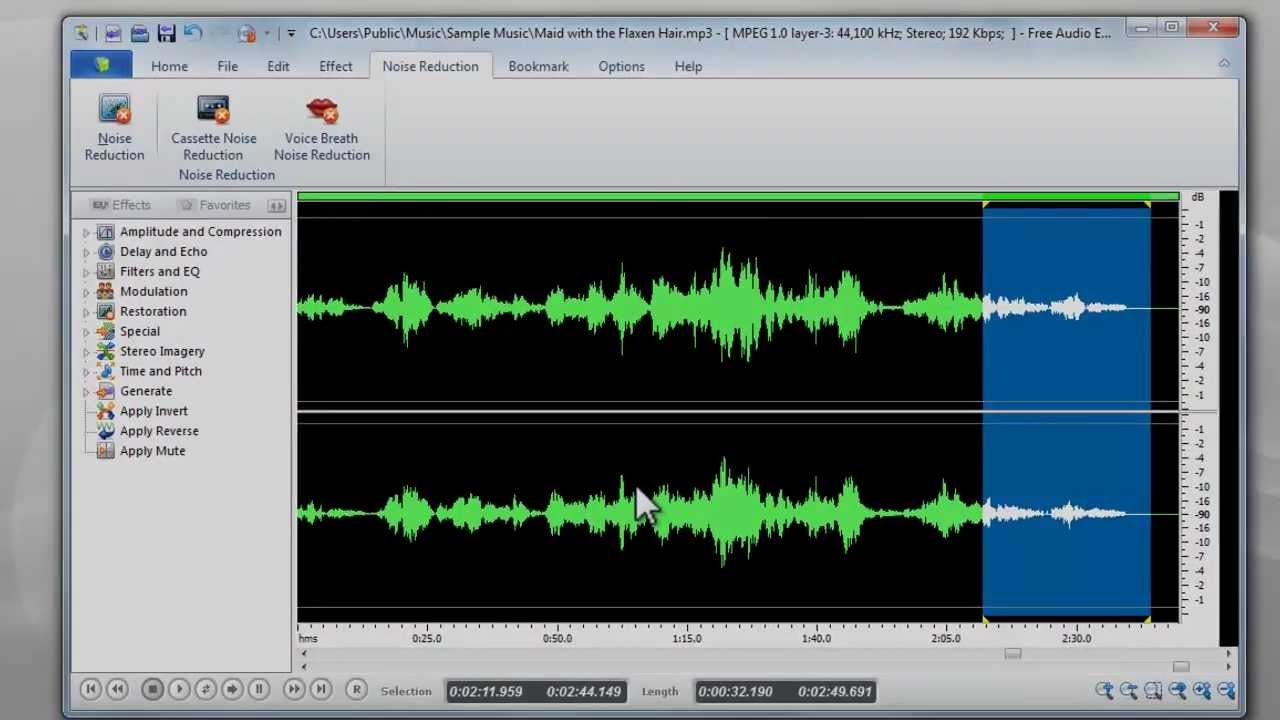

Once you understand the nature of background noise, the next crucial step in audio editing is to accurately identify and isolate it. This process allows us to pinpoint exactly what we need to remove and to select the most effective sections of the audio for noise reduction. Without precise identification, attempts at removal can inadvertently affect the desired audio content, leading to an unnatural or degraded sound.Visual inspection of an audio waveform provides initial clues about the presence and nature of background noise.

Different types of noise manifest as distinct visual patterns, offering a starting point for analysis. By combining this visual information with careful listening, editors can develop a comprehensive understanding of the noise characteristics.

Visual Identification of Noise Patterns

Audio editing software displays sound as a waveform, a graphical representation of the audio signal’s amplitude over time. Analyzing these visual patterns can reveal the presence of consistent or intermittent noise.

- Constant Hum or Buzz: This type of noise, often from electrical interference, typically appears as a steady, low-frequency undulation across the waveform. It might look like a consistent, subtle ripple, even when no speech or desired sound is present.

- Hiss: Broadband noise like tape hiss or air conditioning noise often shows up as a consistent, fine-grained texture across the waveform, particularly in quieter sections. It might appear as a slightly elevated baseline of activity, without distinct peaks.

- Clicks and Pops: These transient noises are visible as sharp, sudden spikes or dips in the waveform, often appearing as very narrow, tall peaks or deep troughs. Their distinct shape makes them relatively easy to spot.

- Background Speech or Music: Unwanted dialogue or music will appear as more complex waveform patterns, mirroring the structure of human speech or musical arrangements. These are usually discernible by their rhythmic and varied amplitudes.

Listening for Specific Noise Characteristics

While visual cues are helpful, the human ear is often the most sensitive tool for identifying subtle or complex noise. By actively listening for specific sonic qualities, you can better characterize the background noise.

- Frequency Analysis: Certain noises are dominant in specific frequency ranges. For instance, a low-frequency hum might be felt more in the bass frequencies, while a high-frequency hiss is more prominent in the treble. Using a spectrum analyzer in your audio software can visually confirm these dominant frequencies, showing them as peaks in the frequency graph.

- Timbre and Texture: Describe the “feel” of the noise. Is it a smooth, airy hiss? A harsh, metallic buzz? A muffled rumble? These descriptions help in identifying the source and how to best address it.

- Consistency: Is the noise constant throughout the recording, or does it vary? Constant noise is often easier to remove than intermittent noise like door slams or coughs.

Isolating a Section of Background Noise

To effectively remove background noise, you need to isolate a segment of the audio that containsonly* the noise, without any of the desired speech or sounds. This sample is then used by noise reduction algorithms.

- Locate Silence: Carefully listen through your audio recording for sections where there is no dialogue, music, or other intended sound. These are typically found at the beginning or end of a recording, or in pauses between spoken words.

- Visual Confirmation: Once a potential “silent” section is identified by ear, visually examine the waveform. Look for a period where the amplitude is significantly lower than the desired audio. Ideally, this section should exhibit the characteristic patterns of the background noise you identified.

- Select and Trim: Use your audio editor’s selection tools to precisely select this segment of audio. It’s important to select enough of the noise to be representative, but not so much that it includes unintended sounds. Trim away any surrounding audio that might contaminate the noise sample.

Importance of a Representative Noise Sample

The effectiveness of most noise reduction techniques hinges on the quality and representativeness of the isolated noise sample. A good sample is the foundation for successful noise removal.

A representative noise sample accurately reflects the specific characteristics of the background noise present in the entire recording.

- Accurate Noise Profile: Noise reduction software analyzes the selected sample to build a “noise profile.” This profile tells the software what the noise sounds like in terms of its frequency content and amplitude. If the sample doesn’t accurately represent the noise throughout the recording, the software might remove the wrong frequencies or incorrectly affect the desired audio.

- Avoiding Artifacts: Using a contaminated sample (one that includes speech or other desired sounds) can lead to audio artifacts. These are unwanted sonic distortions that can make the processed audio sound unnatural, “watery,” or “metallic.”

- Handling Variable Noise: If the background noise changes significantly throughout the recording (e.g., a fan speed changes), a single, static noise profile might not be sufficient. In such cases, you might need to use more advanced techniques or multiple noise profiles. However, for most common scenarios, a single, well-chosen sample is critical.

Software and Tools for Noise Reduction

Having understood the nature of background noise and how to identify it, the next crucial step in audio editing is selecting the right tools. Fortunately, a wide array of software and plugins are available, catering to various skill levels and budgets, each offering distinct approaches to noise reduction.The effectiveness of noise reduction often hinges on the capabilities of the software you employ.

From comprehensive Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) that include built-in noise reduction features to specialized plugins offering granular control, the options are diverse. Understanding these tools will empower you to make informed decisions for your audio projects.

Popular Audio Editing Software for Noise Reduction

Numerous audio editing applications offer robust noise reduction capabilities, making them indispensable for podcasters, musicians, filmmakers, and audio engineers. These programs provide a comprehensive suite of tools for manipulating and cleaning audio.

- Adobe Audition: A professional-grade audio editor known for its powerful noise reduction tools, including spectral frequency display for precise identification and removal of noise. It offers a variety of noise reduction effects, from simple noise gating to advanced spectral repair.

- Audacity: A free and open-source audio editor that is highly popular among beginners and hobbyists. It provides a straightforward noise reduction effect that can significantly improve audio quality by removing consistent background hums or static.

- Reaper: A highly customizable and affordable DAW favored by many for its flexibility and extensive plugin support. While it doesn’t have a dedicated “noise reduction” button, its built-in tools and vast plugin ecosystem allow for sophisticated noise management.

- Logic Pro X: A professional DAW for macOS users, offering a range of built-in audio processing tools, including effective noise gate and noise reduction plugins, alongside advanced editing features.

- Pro Tools: Considered an industry standard in professional audio production, Pro Tools offers powerful built-in tools and a vast array of third-party plugins for comprehensive noise reduction and audio restoration.

Free versus Paid Audio Editing Applications for Noise Reduction

The choice between free and paid audio editing applications often comes down to the depth of features, precision, and the overall workflow required. Both categories offer valuable tools for noise reduction, but with differing levels of sophistication.

Free applications like Audacity are excellent starting points, offering accessible and effective noise reduction for common issues such as steady hums or background hiss. Their noise reduction effect is generally straightforward to use, making it ideal for quick cleanups and less demanding projects. However, they may lack the advanced algorithms and granular control found in paid software, which can be crucial for tackling complex noise profiles or preserving subtle audio details.

Paid professional DAWs and specialized audio editors, on the other hand, provide more advanced noise reduction techniques. These often include spectral editing, which allows for the visual identification and removal of specific noise frequencies, offering a much higher degree of precision. They also tend to have more nuanced algorithms that can reduce noise with less impact on the desired audio signal, preserving the integrity of speech or music.

For professional-grade audio restoration and situations where even minor background disturbances need to be eliminated, paid software is typically the preferred choice.

Types of Built-in Noise Reduction Tools in DAWs

Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) commonly include a variety of built-in tools designed to address different types of background noise. These tools are integrated into the software’s core functionality, providing immediate access for audio engineers and producers.

- Noise Gate: This tool automatically silences the audio signal when it falls below a certain threshold. It’s effective for removing background noise that occurs between spoken words or musical phrases, such as room ambience or subtle hums. The gate can be set to open only when the desired signal is present and close when it drops below a specified level, effectively cutting out the noise floor.

- Noise Reduction (or De-noise): This is a more comprehensive tool that analyzes a section of the audio identified as containing only noise. It then uses this “noise profile” to subtract that specific noise from the entire track. This is particularly effective for consistent background noises like air conditioning hum, fan noise, or electrical buzz.

- Hum Removal: Specifically designed to target and eliminate low-frequency hums, often caused by electrical interference (e.g., 50Hz or 60Hz mains hum). These tools typically use filters to precisely identify and attenuate these specific frequencies.

- Click and Pop Removal: These tools are designed to detect and eliminate transient noises such as clicks, pops, and crackles, which can arise from vinyl record playback, digital glitches, or microphone handling. They often work by identifying the sharp, sudden amplitude changes characteristic of these sounds.

- Spectral Editing: While not always a “built-in” effect in the same way as a gate, many modern DAWs offer spectral editing views. This allows users to visualize the audio spectrum over time and manually select and attenuate or remove specific unwanted sounds, like a distant siren or a chair squeak, with remarkable precision.

Dedicated Plugins for Advanced Noise Removal

Beyond the built-in capabilities of DAWs, a market exists for specialized plugins that offer even more sophisticated and targeted noise reduction solutions. These plugins are often developed by companies focusing exclusively on audio restoration and processing.

These dedicated plugins leverage advanced algorithms and machine learning to achieve results that can be difficult to obtain with standard DAW tools. They are designed to tackle challenging noise scenarios, such as removing complex background ambience, specific unwanted sounds within speech, or dealing with heavily degraded recordings.

Examples of highly regarded dedicated noise reduction plugins include:

- iZotope RX: Widely considered the industry standard for audio repair and restoration. RX offers a suite of modules, each designed for specific tasks like De-noise, Spectral De-noise, Dialogue Isolate, De-reverb, and more. Its spectral editor is particularly powerful, allowing for precise visual selection and removal of unwanted sounds.

- Waves Clarity Vx Pro: This plugin uses advanced AI to intelligently remove background noise and reverb from voice recordings. It’s known for its speed and effectiveness in cleaning up dialogue in real-time, making it a favorite for voice-over artists and podcasters.

- Accusonus ERA Bundle (now part of Meta): This bundle offers a collection of user-friendly plugins focused on specific audio repair tasks, including ERA Noise Remover, ERA Voice Deepener, and ERA De-Esser. They are designed for quick, one-knob solutions that deliver impressive results.

- Cedar Audio: A company renowned for its high-end audio restoration hardware and software. Their plugins, such as Cedar Retouch and Cedar Voice, are used in forensic audio analysis and high-profile restoration projects for their unparalleled ability to remove noise and artifacts without damaging the original audio.

General Techniques for Noise Removal

Once we understand the nature of background noise and how to identify it, we can delve into the practical methods for its removal. This section explores several key techniques that audio editors employ to clean up recordings, ranging from simple threshold-based adjustments to sophisticated algorithmic processes. Mastering these techniques will significantly enhance the clarity and professionalism of your audio.

Noise Gating

Noise gating is a fundamental technique used to reduce or eliminate unwanted background noise during periods of silence or low signal. It functions by setting a threshold level; when the audio signal falls below this threshold, the gate automatically reduces or mutes the output. This is particularly effective for removing persistent hums, hiss, or ambient room noise that becomes audible when no desired audio is present.The application of a noise gate involves setting a few key parameters:

- Threshold: This is the level at which the gate opens (allows signal through) or closes (mutes signal). Setting this too high might cut off desired audio, while setting it too low will allow noise to pass.

- Attack: This determines how quickly the gate opens once the signal crosses the threshold. A fast attack is generally preferred for audio to avoid cutting off the initial part of a sound.

- Release: This controls how quickly the gate closes after the signal drops below the threshold. A slower release can create a more natural fade-out and prevent abrupt muting, but too slow a release might let noise back in.

- Hold: Some gates offer a hold parameter, which keeps the gate open for a specified duration after the signal drops below the threshold, providing a smoother transition.

- Range/Reduction: This setting dictates how much the signal is attenuated when the gate is closed. A full mute is a range of infinity, while a smaller range might simply reduce the noise level without complete silence.

When applied judiciously, noise gating can dramatically improve the intelligibility of speech and the overall quietness of a recording during pauses.

Equalization (EQ) for Noise Attenuation

Equalization, or EQ, is a powerful tool for shaping the tonal balance of audio. In the context of noise reduction, EQ can be used to surgically remove or reduce specific frequencies that are characteristic of unwanted background noise. Many types of noise, such as mains hum, fan noise, or air conditioning, occupy distinct frequency bands.The process of using EQ for noise reduction typically involves:

- Identifying Noise Frequencies: This often requires listening carefully to the noisy sections of the audio or using a spectrum analyzer to visualize the frequency content. Common noise frequencies to target include:

- 50 Hz or 60 Hz (and their harmonics) for mains hum.

- Higher frequencies (e.g., above 10 kHz) for hiss.

- Mid-range frequencies for buzzing or electrical interference.

- Applying a Cut: Once the problematic frequencies are identified, a parametric EQ can be used to create a narrow “notch” filter that significantly reduces the level of those specific frequencies. The depth and width (Q factor) of the notch are crucial. A very narrow notch is ideal for removing a single, distinct frequency without affecting the surrounding audio.

- Broadband Noise Reduction: For more diffuse noise like hiss or general room ambience, broader EQ cuts in specific frequency ranges might be necessary. However, this approach must be used with caution, as excessive EQ can alter the desired audio’s character.

For instance, if a recording has a noticeable 60 Hz hum from electrical equipment, a skilled audio engineer would use an EQ to apply a sharp cut precisely at 60 Hz and potentially at 120 Hz and 180 Hz (its harmonics) to effectively eliminate this persistent noise.

Spectral Editing

Spectral editing represents a more advanced and precise approach to noise removal, offering a visual representation of audio over time and frequency. Unlike traditional editing tools that operate on the waveform, spectral editors display audio as a spectrogram, where the horizontal axis represents time, the vertical axis represents frequency, and the color or intensity represents the amplitude of the sound at that specific time and frequency.The functionality of spectral editing for noise removal is highly granular:

- Visual Identification: Unwanted noise often appears as distinct patterns or blobs on the spectrogram. For example, a sharp click might be a vertical line, while a continuous hum could be a horizontal band.

- Targeted Selection: Users can visually select specific areas of noise on the spectrogram, isolating it from the desired audio. This selection can be incredibly precise, targeting only the problematic sound.

- Noise Reduction Algorithms: Once selected, specialized spectral repair tools can be applied. These tools analyze the selected noise and intelligently reconstruct the underlying audio, effectively “erasing” the noise without leaving audible artifacts. Common spectral editing tools include:

- DeClick: For removing transient noises like clicks and pops.

- DeCrackle: For addressing more sustained crackling sounds.

- DeHum: For removing mains hum.

- DeNoise: A more general tool for reducing broadband noise.

- Intelligent Reconstruction: The software uses sophisticated algorithms to analyze the surrounding “clean” audio and fill in the gaps created by the removed noise, aiming for a seamless restoration.

Spectral editing is invaluable for removing complex or intermittent noises that are difficult to address with other methods, such as a bird chirp during a voice recording or a sudden cough in a musical performance.

Noise Reduction Algorithms

At the core of many noise reduction tools lie sophisticated algorithms designed to distinguish between desired audio signals and unwanted noise. These algorithms typically operate by analyzing a “noise profile” – a sample of the background noise taken when no desired audio is present.The principle behind these algorithms can be understood through the following steps:

- Noise Profiling: The software first analyzes a segment of pure noise to create a detailed fingerprint of its frequency and amplitude characteristics. This profile serves as a reference.

- Signal Analysis: The algorithm then processes the entire audio recording, comparing segments of the signal against the established noise profile.

- Reduction: When the algorithm detects audio characteristics that match the noise profile, it applies a reduction. This reduction can be applied in various ways, such as:

- Subtractive Synthesis: The algorithm essentially “subtracts” the identified noise components from the signal.

- Adaptive Filtering: The algorithm continuously adjusts filters to attenuate frequencies and amplitudes that correspond to the noise, while allowing the desired signal to pass through.

- Parameter Control: Advanced algorithms allow users to control parameters such as the amount of reduction, the sensitivity of detection, and the characteristics of the “clean” signal to prevent artifacts. Common parameters include:

- Reduction Amount: How much the noise is attenuated.

- Sensitivity: How aggressively the algorithm identifies noise.

- Spectral Decay/Smoothing: Controls how the algorithm handles frequency variations in the noise.

A common example of this is a “denoiser” plugin in a digital audio workstation (DAW). After capturing a few seconds of the background hiss from a microphone in an untreated room, the plugin analyzes this sample and then applies its learned profile to the entire recording, significantly reducing the perceived hiss. However, it’s crucial to avoid over-processing, which can lead to a “watery” or “metallic” sound, often referred to as “musical noise” artifacts.

Step-by-Step Procedure for Noise Reduction

Successfully removing background noise from your audio recordings is a process that, while sometimes intuitive, benefits greatly from a structured approach. This section Artikels a typical workflow for applying noise reduction techniques, focusing on the practical steps involved in using common software tools. By following these steps, you can achieve cleaner audio while preserving the integrity of your desired sound.This step-by-step guide will walk you through the common process of using noise reduction plugins within audio editing software.

We will cover the crucial stages of identifying and isolating noise, creating a noise profile, applying the reduction, and fine-tuning the settings to achieve optimal results without introducing undesirable artifacts.

Creating a Noise Profile

The cornerstone of most noise reduction processes is the creation of a “noise profile.” This profile is essentially a snapshot of the specific background noise you want to remove. Most noise reduction tools require you to provide them with a segment of your audio that containsonly* the unwanted noise. This allows the software to learn the unique characteristics of that noise.The process typically involves the following:

- Locate a section of your audio recording where the background noise is present but the primary audio signal (like speech or music) is absent or very low. This is often found at the beginning or end of a recording, or during brief pauses.

- Select this segment of audio within your Digital Audio Workstation (DAW) or audio editor.

- Access the noise reduction tool or plugin.

- Within the plugin’s interface, find the option to “Learn Noise Profile,” “Capture Noise,” or a similar command. Click this button while the noise-only segment is selected.

The software will then analyze this selected audio to build a spectral fingerprint of the noise. This profile is what the plugin will use to identify and attenuate similar frequencies and patterns throughout your entire audio file.

Applying Noise Reduction

Once a noise profile has been successfully created, the next step is to apply the noise reduction to the entire audio track or specific sections where noise is problematic. This is where the actual removal of the unwanted sound occurs.The typical workflow for applying noise reduction includes:

- With the noise profile captured, select the entire audio file or the specific segments that require noise reduction.

- Re-open the noise reduction plugin.

- Now, instead of learning a profile, you will use the “Apply,” “Reduce,” or “Process” function.

- The plugin will use the previously learned noise profile to identify and reduce the noise within your selected audio.

It is crucial to understand that noise reduction is not a perfect, one-click solution. Over-application can lead to artifacts, making the audio sound unnatural or “watery.” Therefore, careful adjustment of the reduction levels is paramount.

Setting Appropriate Reduction Levels

Determining the correct amount of noise reduction is a delicate balance. Too little, and the noise will remain noticeable. Too much, and you risk damaging the desirable audio. The key is to find a level that effectively reduces the noise without introducing audible artifacts.Consider the following when setting reduction levels:

- Reduction Amount/Gain Reduction: This parameter controls how much of the identified noise the plugin will attempt to remove. It is often expressed in decibels (dB). Start with a moderate setting, perhaps around 6-12 dB, and gradually increase it while listening.

- Sensitivity/Threshold: Some plugins allow you to set a sensitivity or threshold. This determines how aggressively the plugin identifies noise. A higher sensitivity might catch more noise but also increase the risk of affecting the desired audio.

- Frequency Range: Advanced plugins might allow you to specify frequency ranges for noise reduction. This can be useful if your noise is concentrated in specific parts of the spectrum (e.g., a low hum).

A good practice is to start with conservative settings and incrementally increase them. Listen carefully for any signs of “musical noise” (a ringing or chirping sound) or a loss of clarity in the desired audio.

“The goal of noise reduction is to make the unwanted sound imperceptible, not to eliminate it entirely at the expense of the desired signal.”

Previewing and Comparing Audio

Effective noise reduction relies heavily on your ability to critically listen and compare the processed audio with the original. Most audio editing software and noise reduction plugins offer features to facilitate this comparison, allowing you to make informed decisions about your settings.Best practices for previewing and comparing include:

- Bypass Function: Utilize the “Bypass” or “Enable/Disable” function within the noise reduction plugin. This allows you to instantly switch between the processed audio and the original, making it easy to hear the difference and assess the effectiveness of your adjustments.

- Soloing Sections: Focus on listening to short, representative sections of your audio. This is particularly useful when fine-tuning reduction levels, as you can quickly cycle through different settings on a specific problematic segment.

- A/B Comparison: Some advanced tools offer an A/B comparison feature, where you can toggle between the original and processed versions with a single click or keypress. This is an invaluable tool for making precise judgments.

- Listen in Context: While focusing on specific problem areas is important, also listen to the processed audio in the context of the entire track. This helps ensure that the noise reduction doesn’t create abrupt or unnatural changes in the overall sound quality.

Regularly switching between the original and processed audio will train your ear to identify subtle artifacts and guide you toward the optimal balance between noise removal and audio fidelity.

Advanced Noise Removal Strategies

While basic noise reduction techniques can effectively tackle common issues, more complex audio problems often require specialized approaches. This section delves into advanced strategies that address subtle yet problematic noise types, ensuring pristine audio quality even in challenging scenarios.Moving beyond general noise reduction, these advanced techniques target specific acoustic anomalies and signal degradation. Understanding and applying them can significantly elevate the clarity and professionalism of your audio productions.

De-Reverberation Techniques

Reverberation, often perceived as echo or room reflections, can make audio sound distant, muddy, and unprofessional. De-reverberation aims to reduce these unwanted reflections, bringing the direct sound of the source forward and improving intelligibility. This is particularly crucial in recordings made in untreated or acoustically challenging spaces.There are several ways to approach de-reverberation:

- Spectral Editing: This method involves analyzing the audio spectrum and identifying the resonant frequencies associated with the reverberation. By selectively attenuating these frequencies, the unwanted reflections can be diminished. Tools like iZotope RX offer advanced spectral repair capabilities that allow for precise manipulation of these resonant tails.

- Algorithmic De-Reverb Plugins: Dedicated plugins utilize complex algorithms to analyze the early reflections and the reverberant tail. They work by identifying the characteristics of the room’s impulse response and applying an inverse filter to counteract it. These plugins often provide controls for decay time, diffusion, and the balance between direct and reverberant sound.

- Convolution Reverb Removal: In some cases, particularly with sampled audio or pre-recorded music, the reverberation might be a convolution effect. In such instances, specialized deconvolution algorithms can be employed to attempt to reverse the convolution process.

It’s important to note that aggressive de-reverberation can sometimes introduce artifacts or an unnatural “dry” sound. A balanced approach, focusing on reducing the most prominent reflections, is usually most effective.

De-Humming and De-Clicking Processes

Specific types of noise, such as electrical hum and transient clicks, require dedicated processing to be effectively removed without damaging the desired audio.

De-Humming

Electrical hum is a common issue, often manifesting as a consistent low-frequency tone (typically 50Hz or 60Hz, depending on the region’s power grid) and its harmonics.

- Notch Filters: The most straightforward method is to use narrow notch filters precisely tuned to the fundamental frequency of the hum and its multiples. These filters significantly attenuate the hum frequency while minimally affecting the surrounding audio.

- Dedicated De-Hum Plugins: More sophisticated de-hum plugins analyze the hum’s characteristics and can adaptively remove it. They often offer controls to specify the hum frequency, its order (harmonics), and the amount of reduction.

When using notch filters, it’s crucial to identify the exact frequency of the hum. Many audio editors have spectrum analyzers that can help pinpoint this.

De-Clicking

Clicks are short, sharp transient sounds that can be caused by various issues, including vinyl surface noise, digital glitches, or microphone handling.

- Transient Detection and Removal: De-clicking algorithms work by detecting these short, high-amplitude transients. Once identified, they can be either attenuated, replaced with a short segment of silence, or interpolated from the surrounding audio.

- Manual Spectral Editing: For stubborn or isolated clicks, manual spectral editing can be highly effective. Zooming into the waveform and spectrum allows you to visually identify the click and surgically remove or attenuate it.

The effectiveness of de-clicking depends on the nature and density of the clicks. Severe click damage might be difficult to remove completely without audible artifacts.

Transient Shaping and Its Role in Noise Management

Transient shaping is a powerful tool that manipulates the attack and sustain of sounds. While not a direct noise reduction tool, it plays a crucial role in noise management by subtly altering the sonic character of audio to make noise less prominent or to enhance the desired signal.Transient shaping allows you to:

- Soften Transients: By reducing the initial attack of a sound, you can make percussive elements or sudden noises less sharp and intrusive. This can help to “smooth out” harsh noises or reduce the impact of unwanted clicks and pops by making them less abrupt.

- Enhance Sustains: Conversely, by increasing the sustain, you can make quieter elements of the desired signal more audible. This can be useful if your primary audio is very quiet and the background noise is more consistent, as it can help to bring up the desired signal without proportionally increasing the noise floor.

- Reduce Percussive Noise: In situations where unwanted percussive noises are present (e.g., keyboard typing, chair squeaks), transient shaping can be used to reduce the initial impact of these sounds, making them less distracting.

Transient shaping works by analyzing the amplitude envelope of a sound and providing controls to adjust the loudness of the attack (transient) and the sustain (body) of the sound independently.

Workflow for Combining Multiple Noise Reduction Techniques

Achieving optimal noise reduction often involves a strategic combination of different techniques. A well-designed workflow ensures that each tool is applied appropriately and that the cumulative effect is beneficial without introducing unwanted artifacts.Here is a general workflow for combining multiple noise reduction techniques:

- Initial Assessment and Noise Profiling: Before applying any processing, carefully listen to the audio and identify all types of noise present. Record a “noise profile” if using noise reduction plugins that require it, focusing on a section of pure background noise.

- Targeted Noise Removal (Specific to General):

- Start with the most specific and aggressive noise reduction techniques. For example, if you have a prominent electrical hum, address that first with a de-hum plugin or notch filters.

- Next, tackle other specific transient noises like clicks or mouth clicks using de-clicking tools or spectral editing.

- Address reverberation or echo using de-reverberation plugins.

- General Noise Reduction: After addressing specific noises, apply a general broadband noise reduction tool to reduce the overall noise floor. Use this tool judiciously to avoid “musical noise” or a “watery” sound.

- Transient Shaping (Optional but Recommended): If the desired audio has overly sharp transients that are contributing to perceived harshness or if unwanted percussive noises remain, use transient shaping to subtly adjust the attack and sustain. This can help to make the overall sound more pleasing and less noisy.

- De-Essing (If Applicable): If sibilance (harsh “s” sounds) is an issue, apply a de-esser.

- Final Listening and Tweaking: Listen critically to the processed audio. Make small adjustments to each processing step as needed. Sometimes, slightly backing off on one setting can yield better results than pushing it too hard. It’s often beneficial to A/B test your processing to compare the original with the processed audio.

The order of operations can sometimes matter. For instance, it might be beneficial to de-reverb before applying broadband noise reduction, as the reverberant tail can sometimes contain noise that gets amplified by the noise reduction process. Experimentation and careful listening are key to finding the best sequence for your specific audio.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Noise Reduction

![Best Audio Editors to Remove Background Noise from Audio [Windows] Best Audio Editors to Remove Background Noise from Audio [Windows]](https://tipsandtrik.web.id/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/remove-background-noise7.jpg)

Successfully reducing background noise in your audio recordings is a crucial skill, but it’s easy to stumble into common traps that can degrade the quality of your desired signal. Understanding these pitfalls and how to avoid them will help you achieve cleaner, more professional-sounding audio without sacrificing its integrity. This section will guide you through the most frequent mistakes and offer practical advice for navigating them.Over-processing audio is perhaps the most significant and detrimental pitfall.

When noise reduction tools are applied too aggressively, they can introduce undesirable artifacts, such as a “watery” or “metallic” sound, or even completely erase subtle nuances of the original recording. This can leave your audio sounding unnatural, robotic, and less engaging for the listener. It’s essential to remember that the goal is to reduce noise, not to obliterate it at the expense of the primary audio.

Recognizing the Signs of Over-Processing

Over-processing audio can manifest in several distinct ways, often making the audio sound worse than the original noisy recording. Being able to identify these signs is the first step in preventing them.

- Unnatural Timbre: The fundamental character of voices or instruments can be distorted, sounding hollow, thin, or overly processed.

- “Gating” or “Pumping” Artifacts: These are rhythmic fluctuations in volume that occur when the noise reduction aggressively cuts off sound between desired audio segments.

- Loss of Transients: Sharp, percussive sounds (like the “t” or “p” in speech, or the attack of a musical instrument) can be softened or completely removed, making the audio sound dull.

- Increased Distortion: Aggressive noise reduction can sometimes introduce or exacerbate existing distortion in the audio signal.

- “Underwater” Effect: This is a common description for audio that has been heavily processed, often characterized by a muffled and indistinct quality.

Strategies for Maintaining Natural Audio Character

Preserving the natural quality of your original audio while still effectively reducing noise requires a delicate balance and a mindful approach. Implementing these strategies will help you achieve a cleaner sound without compromising the authenticity of your recordings.

- Use Noise Reduction Sparingly: Apply the least amount of processing necessary to achieve an acceptable level of noise reduction. It’s often better to leave a small amount of subtle background noise than to over-process.

- Target Specific Frequencies: Instead of applying broad noise reduction, try to identify the specific frequencies where the noise is most prominent and address them individually. This allows for more precise control.

- Employ Multiple Passes with Lower Settings: Instead of one aggressive pass, consider making several passes with much lower reduction settings. This can often yield more transparent results.

- Listen Critically on Different Playback Systems: What sounds acceptable on one set of headphones might be glaringly obvious on another. Test your processed audio on various speakers and headphones to ensure it holds up.

- Utilize Dynamic Processing: Tools like expanders or gates can be used subtly to reduce noise between spoken words or musical phrases, rather than a constant reduction across the entire track.

- Embrace Noise Profiling Carefully: When using noise profiling tools, ensure your profile is representative of the noise you want to remove and doesn’t inadvertently capture parts of the desired signal.

Balancing Noise Reduction with Audio Fidelity

Achieving the optimal balance between noise reduction and preserving audio fidelity is the ultimate goal. This involves understanding the trade-offs and making informed decisions at each step of the process.

The aim of noise reduction is to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio without negatively impacting the signal itself.

This principle highlights the core challenge. Aggressive noise reduction will inevitably reduce the fidelity of the desired audio. Therefore, the process is about finding the sweet spot where noise is acceptably minimized, and the original signal remains as intact and natural as possible. This often means accepting that perfect silence might not be achievable without sacrificing quality, and that a small amount of residual, unobtrusive noise can be preferable to overly processed audio.

Careful listening, iterative adjustments, and a thorough understanding of the tools at your disposal are key to mastering this balance.

Practical Applications and Examples

![How to Remove Background Noise from Audio [10 Ways] How to Remove Background Noise from Audio [10 Ways]](https://tipsandtrik.web.id/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/remove-background-noise-from-audio-audition.jpg)

Understanding the theoretical aspects of noise reduction is crucial, but seeing how these techniques are applied in real-world scenarios truly solidifies their value. This section delves into specific situations where audio noise is a common problem and explores the most effective strategies for tackling it. By examining diverse audio elements and illustrating the impact of noise reduction, we can gain a comprehensive appreciation for its transformative power.The following table provides a quick reference for common audio scenarios, the types of noise typically encountered, and the recommended techniques for their removal.

This serves as a practical guide for selecting the most appropriate approach based on your specific needs.

| Scenario | Primary Noise Type | Recommended Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Podcast Recording | Room Ambience, HVAC | Spectral Editing, Noise Gate |

| Music Vocal Track | Hiss, Hum | Noise Reduction Plugin, EQ |

| Field Recording | Wind Noise | Specialized Filters, Aggressive Reduction |

| Voiceover for Video | Plosives, Background Chatter | De-esser, Noise Gate, Spectral Editing |

| Archival Audio Restoration | Crackle, Pops, Tape Hiss | Dedicated Restoration Software, Spectral Repair |

Applying noise reduction effectively often requires tailoring the process to the specific audio element being treated. Different types of sounds have unique characteristics, and understanding these nuances allows for more precise and impactful noise removal.

Noise Reduction for Dialogue and Voiceovers

Dialogue and voiceovers are perhaps the most common elements where clean audio is paramount for intelligibility and listener engagement. Background noise, even subtle, can distract from the spoken word and reduce the perceived quality of the production.For dialogue recorded in a typical room setting, the primary culprits are often HVAC system hum, refrigerator buzz, or general room ambience. Spectral editing is highly effective here, allowing you to visually identify and surgically remove these persistent tonal noises from the frequency spectrum.

A noise gate can also be beneficial to automatically silence the audio when no voice is present, effectively masking residual background noise between sentences. When dealing with plosives (those harsh “p” and “b” sounds that create a puff of air), a de-esser plugin can be used, though it’s more commonly associated with sibilance. For plosives, careful microphone technique during recording is the first line of defense, but spectral editing can also help attenuate the low-frequency impact of these sounds.

Noise Reduction for Musical Instruments and Vocals

In music production, maintaining the integrity of the original performance is key. Noise reduction techniques should be applied judiciously to avoid degrading the desired audio.For vocal tracks, common issues include tape hiss from older recording equipment or electrical hum. Dedicated noise reduction plugins are invaluable here. These plugins analyze a “noise profile” (a section of audio containing only the noise) and then attempt to remove that specific noise from the entire track.

Equalization (EQ) is also a powerful tool. For instance, a high-pass filter can remove low-frequency rumble, while carefully reducing frequencies where hiss is prominent can make a significant difference without overly affecting the vocal’s clarity. For instrumental tracks, the approach will depend on the instrument. For example, guitar amp hum might be addressed with a noise gate or specialized plugins designed for amplifier noise, while the subtle noise of acoustic instruments might require more delicate spectral editing.

Noise Reduction for Field Recordings

Field recordings, capturing sound in natural environments, often present the most challenging noise reduction scenarios. Unpredictable elements like wind, traffic, or distant machinery can be pervasive.Wind noise is particularly problematic due to its broadband nature and unpredictable fluctuations. Specialized filters designed to combat wind noise are often necessary. These filters are typically more aggressive than standard noise reduction tools and aim to reduce the low-frequency turbulence associated with wind.

Aggressive reduction might be required, but it must be balanced to avoid creating an unnatural “underwater” sound or artifacts. Careful placement of microphones during recording is the most effective way to minimize wind noise in the first place, using windscreens or blimps. For other environmental noises like traffic or construction, spectral editing can be employed to identify and attenuate specific offending frequencies, though the broadband nature of many environmental sounds makes complete removal challenging.

Illustrative Before-and-After Audio Descriptions

To truly grasp the impact of noise reduction, consider these descriptive examples. Imagine listening to an audio clip where a voiceover is nearly drowned out by the persistent drone of an air conditioner. After applying spectral editing to remove the specific frequency of the HVAC hum and a light noise gate to suppress the remaining ambient noise between spoken words, the voice becomes crystal clear.

The listener can now easily discern every word, and the overall production quality is dramatically improved.Another example involves a delicate acoustic guitar recording marred by a noticeable tape hiss. Before noise reduction, the hiss creates a constant, distracting layer over the music. After applying a targeted noise reduction plugin that has learned the hiss profile, the hiss is significantly reduced or eliminated.

The subtle nuances of the guitar’s strumming and fingerpicking, previously obscured, now come to the forefront, allowing the listener to appreciate the full richness of the performance. The audio now sounds clean and professional, free from the unwanted sonic artifacts.

Preserving Audio Quality During Noise Reduction

Effectively removing unwanted background noise is crucial, but it’s equally important to ensure that the process doesn’t degrade the quality of the desired audio. This section focuses on techniques and considerations to maintain the integrity of your original recording while achieving a cleaner sound. The goal is to strike a balance where noise is minimized without introducing noticeable artifacts or thinning out the primary audio signal.

Minimizing Audible Artifacts

Audible artifacts are unwanted byproducts of the noise reduction process, often sounding like “digital ringing,” “underwater effects,” or a general loss of clarity and naturalness in the voice or music. These occur when the noise reduction algorithm is too aggressive or misinterprets parts of the desired signal as noise. Careful application of settings and understanding the limitations of the software are key to avoiding these issues.

Gradual Reduction Settings

Applying noise reduction too abruptly can shock the audio signal, leading to artifacts. It is far more effective to use gradual reduction settings. This involves applying the noise reduction in smaller increments, allowing the algorithm to make subtle adjustments rather than drastic ones. Many software tools offer parameters like “threshold,” “ratio,” or “strength” that can be adjusted incrementally.

“Think of noise reduction as a gentle sculpting process, not a demolition. Small, precise adjustments yield better results than broad, sweeping changes.”

Auditioning Processed Audio

To truly gauge the impact of your noise reduction settings, it is essential to audition the processed audio at different volume levels. Listening at the intended playback volume is standard, but also check at lower volumes to see if any residual noise becomes more apparent, and at higher volumes to detect any introduced distortion or unnatural characteristics. Many audio editors allow for “bypass” functions, which let you instantly compare the processed audio with the original.

Impact of Sample Rate and Bit Depth

The sample rate and bit depth of your audio files have a significant influence on the effectiveness and potential quality loss during noise reduction. Higher sample rates (e.g., 48kHz, 96kHz) capture more sonic detail, which can be beneficial for both identifying subtle noises and preserving nuances in the desired audio. Similarly, a higher bit depth (e.g., 24-bit) provides a greater dynamic range and more information per sample, allowing for more headroom and precision during processing without introducing quantization errors or excessive noise floor issues.

- Sample Rate: A higher sample rate allows for a more accurate representation of the original sound, meaning the noise reduction algorithms have more data to work with, leading to potentially cleaner results and better preservation of high-frequency details in the desired audio.

- Bit Depth: A higher bit depth provides a wider dynamic range, which is crucial. When you reduce noise, you are essentially altering the amplitude of the signal. With a higher bit depth, there’s more “room” to make these adjustments without clipping or introducing audible quantization noise, preserving the subtle details and quiet passages of your audio.

Summary

As we conclude our exploration of How to Edit Audio to Remove Background Noise, remember that the pursuit of sonic perfection is an art form. By mastering the techniques discussed, from identifying and isolating noise to employing sophisticated software and advanced strategies, you are well-equipped to transform your audio from cluttered to captivating. Embrace these practices to ensure your message resonates with clarity and impact, leaving a lasting impression on your audience.